Sub-sea cables: the Achillis heel of Europe, and the world at large.

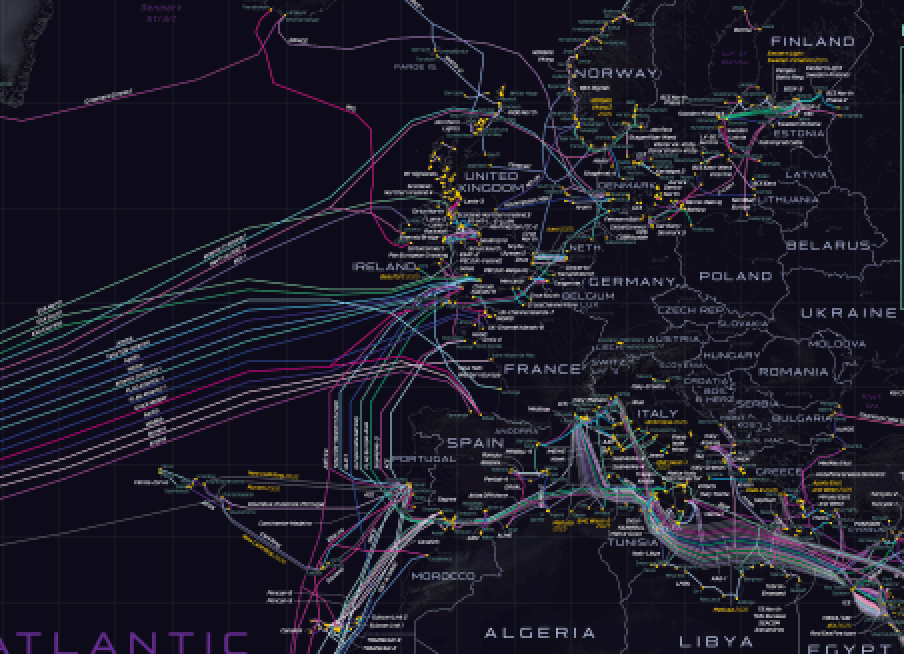

In an era of ever-increasing digital dependence, submarine fibre-optic cable systems have become the invisible lifelines of the global economy. It is estimated that around 97–98% of all international internet traffic traverses these under-sea cables, making them critical infrastructure for everything from video streaming and cloud computing to financial transactions and cross-border services. Major technology firms such as Google, Meta Platforms, Inc. (Facebook), Microsoft Corporation and Amazon Web Services all invest in or utilise these cable systems to connect their global data-centres, support cloud and edge services, and ensure low-latency access across continents. For European firms and users, the continuity of e-commerce, banking, government data exchange, and critical applications depend on these networks working flawlessly—and the fragility of these systems is increasingly under scrutiny in light of geopolitical tensions and technical vulnerabilities.

In July 2025 Recorded future published a threat analysis report that has not really gotten a lot of media coverage, even though it highlights some important risks for our society.

if flags the wider operational, security and strategic dimensions that govern them. The sheer scale of global submarine fibre networks—thousands of kilometres of under-sea cables linking continents, providing essential bandwidth to corporations, data-centres and governments alike is an invisible yet strategic backbone for all digital services. For example, one industry overview lists "Top 100 Subsea Cable Systems" including very long links stretching tens of thousands of kilometres.

A small number of major manufacturing and installation firms—such as Alcatel Submarine Networks (acquired by Nokia) and OMS group— dominate the sector, providing equipment, laying vessels and maintenance capabilities. On the user side, hyperscalers and large telecom carriers are major consumers and increasingly owners of cable capacity—they invest directly in new builds and upgrades to secure latency, capacity and control. Matteo Cadenazzi wrote in an article this September that Google and Facebook have become private custodians of global subsea infrastructure.

The core services and traffic types that traverse these cables are interesting ones: international voice, data interchange, cloud-services connectivity, financial transaction flows, content delivery networks (CDNs), and increasingly critical government and defence communications. The fact that almost all international data enormous flows rely on submarine cables makes them both high-value and high-risk.

These high risks include a number of potential causes such as faults due to anchors dragging, seabed morphology (slides, earthquake), accidental damage, but also a rising concern about malicious or state-sponsored interference. Recent reports of unusual vessel activity near cable routes, regional clusters of cable disruptions (for example in the Baltic Sea) that have prompted speculation about sabotage and eavesdropping. Repair logistics are shown to be non-trivial: limited numbers of repair ships, regulatory and jurisdictional delays when operations cross multiple maritime zones, and the domino effects of congestion when a key route fails.

One notable point is the vulnerability of chokepoints and single-cable dependencies: some landing stations or regions have limited alternative capacity, which means that when a fault occurs the ripple effects are significant—connectivity slows, rerouting costs go up, latency increases, capacity drops, and ultimately service levels suffer. Examples are landing links between Norway–UK, or Finland–Germany, where a disruption can have outsized regional effect. And these are not coincidentally, links that have seen increased suspected activity around them.

Another major point is the business and strategic imperative: operators are investing in new cables, upgrading with higher-capacity fibre pairs, boosting spatial-division multiplexing, and building redundant or alternative routes. Telecom carriers in Europe are partnering with hyperscalers, or building wholy-owned subsea systems (or controlling fibre pairs) to support their global cloud/data strategies. On the manufacturing side, next-generation cables with greater resilience, deeper burial, double-armour in shallow water, and route diversity are emerging.

This infrastructure — while technical and largely invisible — is a strategic asset in the current geopolitical environment. With states recognising the criticality of submarine cables and the risks of disruption, investment in monitoring, defence (physical and cyber), regulatory frameworks, and resilience planning is accelerating. For Europe, this means ensuring its data flows are not only high-capacity but secure, redundant and well-governed.

Why this matters for Europe

From a European perspective, the dependence on subsea cable infrastructure carries both opportunity and vulnerability. Europe's digital economy spans high-volume cloud use, trans-Atlantic data links, interregional traffic (e.g., Nordics ↔ Germany), and external links to Africa, Asia and the Americas. According to recent EU-commissioned material, these cables carry an estimated 97-98% of Europe's international internet traffic. At the same time, Europe records approximately "100 cable fault incidents per year" that affect availability, according to industry commentary.

For European governments, telecom providers and large enterprises, the core issues can be summarised as follows:

- Availability: In Europe, many countries rely on a few cable landing stations and routes. When one link fails—due to an anchor-drag or a seabed slide—the rerouting options may be limited, latency increases, and international business traffic is impacted. The article emphasises that region-specific dependencies (for example, Europe-Nordics, or Europe–Middle East) must be mapped and mitigated.

- Risk: The European maritime domain (Baltic Sea, North Sea, Mediterranean) presents a mix of shallow coastal routes, congested shipping lanes and busy maritime traffic—all of which increase the probability of damage. Moreover, with geopolitical tensions mounting, the above-mentioned surge in concerns about deliberate interference (state-backed or proxy) becomes particularly salient in Europe. The article details how Europe is increasingly scrutinising "shadow fleets" undersea activity.

- Integrity: Europe's regulatory and security frameworks are increasingly treating subsea cables as part of critical infrastructure. Because many cable systems connect Europe to non-European landing points (e.g., Africa, Middle East, Asia), the data flows' confidentiality, integrity and sovereignty are of concern. The article outlines how European actors are beginning to examine who owns the cables, who maintains them, and whether robust encryption and governance are enforced end-to-end.

Given this, Europe is facing a pressing need to move from a reactive posture (repair after fault) to a proactive strategy: route-diverse cable builds, enhanced monitoring and maritime situational awareness, dedicated funding/insurance for resilience, and regulatory frameworks that ensure landing-station security and vendor oversight.